You are here

Book of Mormon Central is in the process of migrating to our new Scripture Central website.

We ask for your patience during this transition. Over the coming weeks, all pages of bookofmormoncentral.org will be redirected to their corresponding page on scripturecentral.org, resulting in minimal disruption.

None of the actions taken against Jesus by the Chief Priests during his final week would have come as any surprise to Jesus. He knew the hearts, the desires, and the intentions of all the actors in this eternal drama. He had heard their questions and arguments many times before.

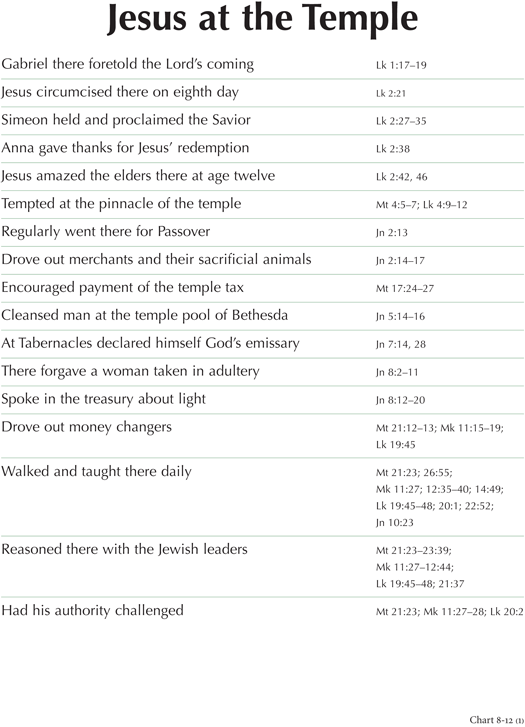

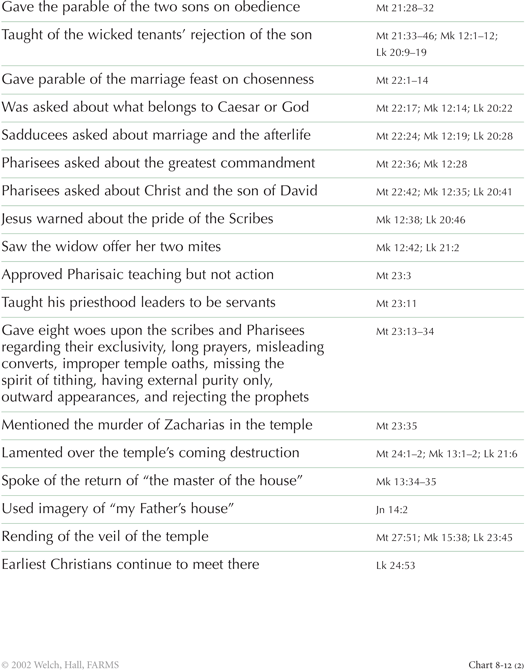

Reentering Jerusalem on Monday morning, the day after his Triumphal entry, Jesus made a beeline directly to the temple. He had been there several times before. He was no stranger there (See Figure 1).

Figure 1 Welch, John W., and John F. Hall. “Jesus at the Temple.” Charting the New Testament. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002, chart 8-12.

There he was immediately asked by the Chief Priests and the elders, “By what authority doest thou these things? And who gave thee this authority?” (Matt. 21:23). Understanding this questioning of Jesus is crucial in understanding the reasons behind the main events in the Easter week. Reinforcing the importance of this critical exchange, it is significant that Matthew, Mark, and Luke all recount this episode almost verbatim (Matt. 21:23–27; Mark 11:27–33; Luke 20:1–8).

Jesus had been asked such questions on other occasions before. At the beginning of Jesus’s ministry, a group of scribes (lawyers) had been sent up from Jerusalem to Galilee to investigate by what “authority” (Mark 1:27) Jesus was performing his miracles. The legal and religious issue was this: If he had performed miracles by the power of God and to God’s glory, his miracles would have been seen as beyond reproach. But if he was doing these miracles “by the prince of the devils” through whom he was “cast[ing] out devils” (Mark 3:22), then Jesus was committing an offense for which he could be put to death. Sorcery, witchcraft, and other forms of working through evil spirits was condemned in several places in the law of Moses. For example, Exodus 22:18 reads, “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live,” and Leviticus 20:27 says, “A man also or woman that hath a familiar spirit, or that is a wizard, shall surely be put to death.”

By asking Jesus this very question once again right after his entry into Jerusalem, conspicuously soon after his raising of Lazarus and the opinion of the Sanhedrin that Jesus and Lazarus were worthy of death (John 11:50, 53; 12:10), the Chief Priests and the elders that Monday morning in the Temple were bringing up a persistent problem. They would have been acting with a strong belief that Jesus’s many signs and wonders raised serious legal problems as they were leading people to follow him and his teachings.

But curiously, the Chief Priests did not act immediately. In light of the fact that an order had been issued for the apprehension of Jesus (John 11:57), one wonders why they did not arrest Jesus on the spot. The answer is fairly clear. As they tried to lay hands on him to arrest him “in that very hour” (Luke 20:19), “they feared the multitude” (Matt. 21:46; Mark 12:12; Luke 20:19). Likewise they decided that it would be imprudent for them to answer Jesus’s question back to them, as He asked them how John the Baptist had received his authority, because they “were afraid of the multitude” (Matthew 21:26; Mark 11:32). They even worried that “all the people will stone us” (Luke 20:6), because the people believed John to be a prophet.

When the chief priests declined to answer Jesus, he chose to speak to them in parables. Before telling them his parable of the Wicked Tenants, he first gave a short parable that is found only in the Gospel of Matthew. I call it the Parable of the Willing and Unwilling Two Sons.

Deeply valuable symbolism is embedded in all of Jesus’s parables, and his parable of the willing and unwilling two sons in Matthew 21 is no exception. What does this parable have to do with answering their demand to know: “By what authority doest thou these things? and who gave thee this authority?” (Matt. 21:23). This simple story is about a certain man who had two sons. When asked to go down and work in the vineyard, the first son initially refused, but then he went. The other son initially said yes (or so it seems), but then for some unstated reason does not go (21:28-30).

While this parable may be useful in parenting, it would seem that, in this context, Jesus may well have been talking in veiled terms about something much more fundamental. Indeed, in speaking about Jesus’s parables in Luke 15, Joseph Smith once taught: “I have a Key by which I understand the scriptures—I enquire what was the question which drew out the answer?”1 Thus, by focusing on the questions asked by the Chief Priests about Jesus’s authority, Joseph’s key unlocks the deeper meaning of this parable in Matthew 21:28–31.

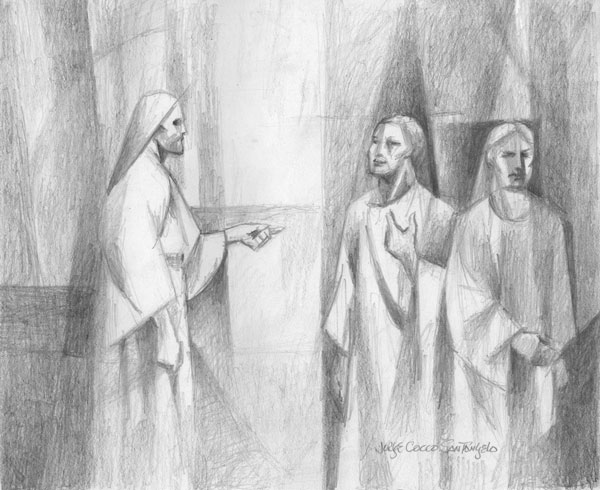

The following is a shortened version of my chapter about this parable in the collection of essays in honor of Robert L. Millet, Let Us Reason Together, published in 2016 by the BYU Religious Studies Center, and also the chapter in John W. and Jeannie S. Welch, The Parables of Jesus: Revealing the Plan of Salvation, published in 2019 by Covenant Communications. In the latter is found this painting by Jorge Cocco (See Header Image above, also Figures 2, 3), that illustrates this immortal parable.

Figure 2 Study of The Father’s Two Sons, by Jorge Cocco Santangelo. Used by permission of

John W. and Jeannie Welch.

Several significant points are included in this instructive story as this parable takes the question of authority into divine and premortal realms. Involved here is no ordinary father, no ordinary vineyard, or any ordinary pair of sons. Bear with me as I explain.

Two sons were asked by the father. In the end, it becomes clear that this father is not just their father, but God the Father.2 The King James Version chose to supplement the text by inserting the word his in italics when Jesus asks, “Whether of them twain did the will of his father?” (21:31). Nevertheless, the Greek reads, “Which of the two did the will of the father (tou patros)?” While it is possible that the definite article here (tou) can simply be understood as taking “the place of an unemphatic possessive pronoun when there is no doubt as to the possessor”3 and thus allowing the KJV rendition “his father,” Jesus’s wording here may be significant, referring to “the Father” and not just to their father. The wording echoes Jesus’s wording in Matthew 7:21 answering a rhetorical question about who shall enter the kingdom of heaven. The answer: one “who does the will of the Father of mine who is in heaven (tou patros mou).” Thus, the use of the definite article in Jesus’s question to the Chief Priests, “which did the will of the Father” invites readers to see the willing son and his Father in this parable as representing the Father in Heaven and Jesus himself as the one who says “thy will be done” (Matt. 26:42) and who does the Father’s will. The two sons were thus called to serve with authority from God whom they would serve. Those with authority do not take that authority upon themselves but are “called of God, as was Aaron” (Hebrews 5:4).

Next, these two sons were both called to “go” by way of commandment from the father. These invitations came, not as polite requests, but as imperatives, literally, “go [-age] down [hyp-]” (Matthew 21:28, 30). While the word hypage can have a number of meanings, including to “go away,” “withdraw,” “depart,” “go forward,” or simply to “go,” its sense always depends on the context in which it is used. Here, if the setting is in the father’s house, the sons are being asked to leave the comforts of home and go work in the fields; if the setting is in the father’s mansion on a hill, or in heaven, then the sons will be going down, descending, from there.

Moreover, in being asked to go, the two sons were told when and where they were to serve—today, and in the vineyard—so their authority was specific. The message is that those with authority do not have the option of selecting another time or place. They can either respond with a yes or a no, but they cannot modify the father’s request.

Figure 3 Study of The Father’s Two Sons, by Jorge Cocco Santangelo. Used by permission of

John W. and Jeannie Welch.

Beyond these points about the nature of authority, this parable draws its listeners into the heavenly realms. In so doing, this story calls to mind events in the Council in Heaven, where a Father indeed had two very different Sons There Jesus received his commission and authority from the Father.

These heavenly, primeval overtones are more evident in the Greek text of Matthew than in the Latin Vulgate or in typical English translations. The most widely supported Greek texts literally read as follows: “A man had two sons, and going to the first he said, ‘Go down this day to work in the vineyard.’ He answered, ‘Not as I will [ou thelō],’ but then reconciling himself to the task he went. Going to the other, he [the Father] said the same. And he answering said, “I, Lord!’ And he did not go.” The differences between this rendition of the Greek and the usual translations of this text—which is clearly more than a mere fable—may be explained as follows.

The first son initially answered the father’s request by saying, “Ou thelō,” which the KJV translates as “I will not” (emphasis added). But thelō is not a future tense verb. It does not mean “I will not, or shall not.” Ou thelō is a present tense verb, meaning “I don’t want to,” or “I don’t wish to,” or “I’d rather not,” or, idiomatically one might say, “Not (ou) [what or as] I will (thelō).” In Elizabethan English, this could mean “I do not will it,” as does the Latin nolo. But this is not how modern readers hear this crucial word will.4 Doing the Father’s will (thelēma—which is the noun cognate to the verb thelō) is a central theme in the Gospel of Matthew leading up to Christ’s teaching in this parable and immediately beyond (see Matt. 6:10; 7:21; 12:50; 18:14; 26:42). In Gethsemane, as the Savior reconciled and submitted himself to the will of the Father, he said, “Not my will (mē to thelēma mou) but thine be done” (Luke 22:42).

The first son “goes away” or “departs from” (apēlthen) the Father’s presence. This verb is translated simply as “went” in the KJV in Matthew 21:29, 30. This word, along with the Father’s command, “go down” (hypage), may call to mind the condescension or incarnation of Jesus leaving his Father’s presence. These words were used by Jesus himself in referring to his own going away or departure, as a euphemism for his impending death and descent into the spirit prison: “Then said the Jews, Will he kill himself? Because he saith, Whither I go (hypagō), ye cannot come” (John 8:22); and “it is expedient for you that I go away (apelthō)” (John 16:7).

The onerous burden of the work asked by the Father seems to have given even the ultimately submissive first son ample reason for pause. Perhaps this son knew when he was asked to go down that there were or would be wicked tenants in the vineyard who would have already beaten or killed the servants sent by the landowner-father, and now in desperation the father needed a son to send. No wonder even that first son might need to think things over a bit.

At this point in Matthew 21:29, the KJV reads, “but afterward he repented,” which might seem unbecoming of the Savior. But the idea that the first son repented of some sin (an idea which is found in the Latin word paenitentia, the word used at this point in the Latin Vulgate Bible) is actually not necessarily implied in the little parable. This is because the Greek word used here is not the ordinary verb used to mean “repent” (metanoeō). Instead, the word is metamelomai, which does not primarily mean “to repent.” In the Septuagint and in Koine Greek, with rare exception, it means to feel sad about something or to change one’s mind, but not primarily to repent of an offense. In Classical Greek, it means to regret, or simply to change one’s purpose or course of conduct. Thus, translating it as “repented” conveys a different sense and feel. Thus I prefer to translate metamelētheis as “reconciling himself” to the task, as the first son submitted his will to serve in the Father’s plan, even shouldering his daunting task and aligning his own will with that of his Father.

At the same time, there was another son. Most manuscripts call him “the other (ho heteros),” while some call him “the second (ho deuteros).” This son stood in utter contrast to the first. He is more than numerically second; he is of another mind or has some other purpose. He was eager at first, but in the end he would not serve his father.

Significantly when this other son answered, he did not say, “I go, Lord,” as the KJV reads. Here again the King James translators followed the Vulgate, which uses the words “eō (I go), domine (Lord).” The word “go,” however, is italicized in the KJV because it is actually not present in the strongest Greek manuscripts. In almost all ancient NT manuscripts, the other son simply says egō, kurie, “I, Lord.” In ordinary parlance, this might sound something like “Yes, Sir.” But the pronoun egō is significant. For this second son, it seems that it was all about his ego. This is the first word he says. He seems caught up with the fact that he had been called. In this context, what does this word egō entail? “I what? Lord.” “I will gladly go?” “OK, I will [grudgingly] go?” or “I get to go!?” “I have been chosen!?” “I will do it;” I want the glory! Lord.” All of these are possibilities. Moreover, the second and only other word in his reply to his father stiffly calls his own father “Lord,” which may well convey less than close personal love or filial devotion. For whatever reason, that son did not go. He was called, but not chosen.

If the first son is identifiable as Jesus, then the second son in this parable can be understood as Lucifer, his brother. For Latter-day Saints, this identification readily calls to mind the scene in the Council in Heaven in which Jesus was given his commission and authority from the Father. While not exactly the same as in this parable, certain similarities stand out. On that occasion the Father asked, “Whom shall I send?” (Abraham 3:27). In the texts we have, Lucifer then responded with a barrage of six first-person pronouns, “Here am I, send me” (Abraham 3:27; Moses 4:1), adding “I will be thy son, . . . I will redeem all mankind . . .; surely I will do it; wherefore give me thine honor” (Moses 4:1). Jesus, however, simply “answered like unto the Son of Man: Here am I, send me” (Abraham 3:27), adding “Father, thy will be done” (Moses 4:2). These two responses typify the contrast between the course of self-interested unrighteousness and the way of submissive righteousness in answering a call from God. Because Satan sought to usurp God’s own honor, glory, power and authority, Lucifer was cast down (Moses 4:2) and, as in Jesus’ parable to the Jewish leaders, Lucifer did not go. Whether he was not allowed to go or whether he took himself out of the running, the outcome was the same. In either case it is interesting to note, the Father was apparently open to sending either (or perhaps, in some way, both), if they would be willing to be his agents and to do his will within the scope of the authority and assignment given to them.

As temple priests, it is not unreasonable that the chief priests and elders would have known something from traditional sources about the heavenly council in which an eternal plan was established from the foundation of the world.5That primal event would have been well known to the Savior and possibly to his disciples and to others of Jesus’s contemporaries. Indeed, the apostle John knew and testified that the power and authority of Jesus came from the premortal world where Jesus obtained his right to rule on this earth, not to do his own will, but to do the will of the Father. The authority of Jesus was traceable back to “the beginning” (John 1:1), and his judgment was just because he sought to do “the will of the Father” who had sent him (John 5:30).

Moreover, Jesus had taught openly, “For I came down from heaven, not to do mine own will, but the will of him that sent me” (John 6:38), and at the Last Supper, only a few days after his Triumphal Entry in to Jerusalem and his confrontation with the Chief Priests and elders in the Temple, Jesus affirmed to his disciples, “I am in the Father, and the Father [is] in me; the words that I speak unto you I speak not of myself: but [of] the Father” (John 13:10). “I have given unto them the words which thou gavest me” (John 17:8).

So, it would not have been out of character or untimely for Jesus to have taken his disciples privately aside as they returned to Bethany after that Monday in the Temple, at the beginning of Easter Week, to tell to them even more about the source and nature of his authority and to explain to them the meanings of this parable of the willing and unwilling two sons.

On that Monday, for all who had ears to hear, this parable clearly answered the two questions asked by the Chief Priests: “By what authority do you do all these things, and who gave thee this authority?” As Jesus testified: He was called and authorized by God, his Father. Jesus was chosen because of his willingness to submit his will to the will of the Father. And Jesus was empowered to act in the name of the Father as he came down and did the works of righteousness. This clearly distinguished Jesus from the “other” son and his unrighteous devils and unrepentant workers of iniquity.

And just as Jesus began this final week with this parable in Matthew 21 about his calling in the heavenly council at the beginning of mortal time, he will end his public teachings that week with a final set of parables in Matthew 25 about the judgment at the end of times. Those two bookends that Easter week bracket the whole of the Plan of Salvation, from start to finish.

To be continued . . .

- 1. Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook, The Words of Joseph Smith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1980), 161. See also Joseph Fielding Smith, comp., Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, 267–277.

- 2. Arland J. Hultgren, “Interpreting the Parables of Jesus,” 637: “It should go without saying that a father can represent God, and so it is.”

- 3. Herbert Weir Smyth, Greek Grammar (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 1963), §1121.

- 4. H. W. Fowler, A Dictionary of Modern English Usage (London: Oxford University Press, 1926), 729.

- 5. They may have known of the pattern of authoritative callings and the heavenly council from several passages, including 1 Kings 22:19–23; Psalms 82:1; 110:3; Isaiah 9:5 LXX; Jeremiah 23:18; Daniel 7:9–14; Amos 3:7; 1 Enoch 12:3–4. See John W. Welch, “The Calling of a Prophet,” in The Book of Mormon: First Nephi, the Doctrinal Foundation, eds. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate (Provo: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1988), pp. 41, 46. Related scriptures may include: Acts 2:23 (Peter’s text assumes that his audience on the Day of Pentecost knew something of the idea of God’s primordial council and plan [boulēi]); 1 Corinthians 2:7 (Paul speaks as well about the wisdom of God that was ordained before the world was), and Alma 13:3 (Alma speaks of priests being “ordained, having been called and prepared from the foundation of the world”).

Subscribe

Get the latest updates on Book of Mormon topics and research for free